Not too long ago I read a statistic that scared me to death:

70% of blind or visually impaired adults are unemployed.

It might not scare everyone to death, but for me, that statistic was heart stopping. That number and the number of people it represents are huge. But when I read that I wasn’t actually concerned about how many people it impacts. I was only concerned at that moment about two people: my blind sons.

My two sons are blind due to a rare inherited eye disease. When we received the first diagnosis sixteen years ago all I could think of was “He will never play baseball. He will never keep up with other kids. He will never drive.” I thought of all the childhood things my son would miss out on. I sobbed over my visions of him never having a full life. You see, I had never met a blind person before. I had only known of a few blind folks – Helen Keller, Stevie Wonder, Ray Charles. All I actually knew about blindness was nothing at all. Therefore, I expected a life of challenge and hardship. My hopes and dreams for my son were gone.

I had such a bleak expectation of my son’s life ahead that in my devastation I relied completely on the early intervention professionals to create his early education plan; and I treated most of them more as my therapists helping me cope than teachers that would help him thrive. I took all advice as golden because they had spent years in the blindness “world” and I was the newbie. I was so lost in my sorrow of a journey I’d never get to be on that I celebrated anything and everything that remotely looked like that old dream of a sighted life: I cheered when a teacher advised me that Michael had “so much” vision he would fight Braille so just skip it; I was proud to hear that he had such great muscle tone “for a blind child”; I breathed a sigh of relief that no one mentioned the white cane for my little guy.

As I was attempting to climb out of the devastation ditch I was in I came across the story about a man named Erik Weihenmeyer that had recently climbed to the summit of Mount Everest – and he is completely blind. His story began to shift my expectation of what might be possible for my blind sons. If Erik could manage climbing a mountain without sight, surely we could figure out preschool. And when the time came, I believed my son was ready and able to attend a local “regular” preschool and move on to the local public school. I expected he’d survive and we’d figure it all out.

And figure it out we did. We figured out that we should have started Braille instruction earlier. We figured out that he was way behind in cane training. We figured out that we were shoving our son into a sighted world hoping for the best instead of guiding him with the right tools to insure his success.

[Tweet “we were shoving him into a sighted world hoping for the best instead of guiding him to insure success.”]

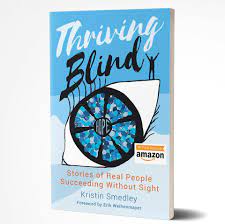

I pressed on and investigated more blind adults that were having success, noting the tools they used. I read about blind runners, musicians, and business leaders. I learned about assistive technology, Braille and mobility training. While my expectations for my sons’ lives were gaining new heights, I began to find that the expectations of blind children in this country are not so high, not high at all as a matter of fact. Remember that statistic I opened this post with, that 70% of blind adults are unemployed? Now consider this:

This is from Michael’s kindergarten Individualized Education Plan (IEP) – “Michael will find his cubby independently 70% of the time.”

My son was going to be expected to achieve only 70% of the time. Hmmm, coincidence or direct correlation of expectations and achievement? When we read that goal in the IEP meeting my husband asked “Does the cubby move around from day to day? Is it a hard thing for even sighted children to find the cubbies?”

No and no. So then, we did not understand why Michael finding his cubby to hang up his jacket only a few times each week would demonstrate success, yet the other children would be doing it 100% of the time. “We don’t want him to fail, Mr. and Mrs. Smedley” they said. “If we hold him to 100% and he misses on one data collection day, it will look as though he isn’t progressing.” It took a while, but we eventually made the case that if he is missing the cubby AT ALL, he is definitely not progressing and things need to be put in place to teach him how to succeed at finding the cubby 100% of the time.

And so began the journey of keeping our expectations of our boys very high – and we hold each of them as well as their education teams accountable. We expected them to learn the Braille code with 100% accuracy. We expected them to learn the computer skills the sighted children were learning with 100% accuracy. We expected them to advocate for themselves, pursue their interests, and be kind, thoughtful and productive community members.

The results? Well, they are each in high school and middle school and are thriving… not just as blind children, but as kids in general. They pursue their passions, they try new things, they excel at schoolwork, they have ups and they have downs. We are still learning the tools of blindness every day and we still constantly reach out to blind role models. Michael is planning for college and Mitchell is planning material for the standup comedy circuit (oh my). I think the only thing they have in common is their passion for student government. Each of them has found teachers, coaches, and other adults that have had high expectations for them and joined their teams in guiding them to their greatness. However, both Michael and Mitchell have had to demonstrate to more than a few folks that blind children are differently able, but more so, differently capable of greatness.

[Tweet “blind children are differently able, but more so, differently capable of greatness”].

I expect my children, the blind and the sighted, to pursue their passions and achieve their dreams. I expect that they will achieve their personal greatness… and you know what? All three of my children expect that of themselves. And that expectation of greatness allows them to be open to figuring out the tools they need and to build a team of support along the way.

I challenge everyone – parents, teachers, coaches, etc – in all communities to heighten our expectations of our children and give them the guidance they need to not just survive life’s challenges…. but to thrive.